I recently saw the Adventure Time episode “James” (season 5, episode 42) for the first time, and I got all excited about the ways in which it quoted 2001: A Space Odyssey. But so far as I’ve been able to tell, nobody on the internet has pointed out this influence yet.

“James” is not a one-to-one recreation of 2001, and the setup of the story has nothing to do with the movie. The episode begins with a flash-forward framing device in the moments right before a funeral, establishing that Finn and Jake are grieving over someone’s death. Then we cut to one week earlier: Finn and Jake and Princess Bubblegum are on a reconnaissance mission in the Desert of Wonder. The camera pans to reveal the fourth member of the team, a goofy weirdo named James whom we have never seen before. Much of the episode’s humor and suspense derives from the understanding that James will die before we catch up with the initial frame story.

A couple incidental details: The mission is being executed in a futuristic tripod-rocket-vehicle, which is slightly unusual for Adventure Time—usually these characters travel on foot (or on Jake’s back) (or on the Morrow). Also, James’s goofy weirdness is mostly expressed by making servo noises with his mouth and pretending to be a robot.

When the characters exit the vehicle to collect surface samples, they don these color-coded environmental suits.

Plenty of people have pointed out that James’s suit casts him as a “redshirt” and therefore doomed. Individual color-coded bodysuits are an affectation we’d normally associate with a Super Sentai homage—but after I saw more of the episode I realized they reminded me of the spacesuits in 2001.

The science mission is cut short when zombies attack the heroes, who retreat into the tripod. Princess Bubblegum asks Finn to come up with a way out. He suggests calling for help on the radio, but Bubblegum says it “looks like the radio’s kerplowed” (although there’s no visual indication of this). James offers to fix it.

The other three characters go into the tripod’s back room, where Jake finds a flare gun. James joins them to say he’s fixed the radio; Bubblegum goes first to check on it. When Finn and Jake join her, they discover the radio is now “all sanched up,” meaning all the wires are cut and it is beyond repair. Finn asks for the flares, but when James brings the box over, it is empty.

The corresponding segment of 2001 goes like this: On a spaceship en route to Jupiter, the HAL 9000 computer intelligence reports to astronauts Frank and Dave that the ship’s AE-35 unit is about to malfunction. (We later discover that without the AE-35, the ship can’t communicate with Earth.) The humans retrieve the unit and find it in perfect working order. HAL says this “could only be attributable to human error.”

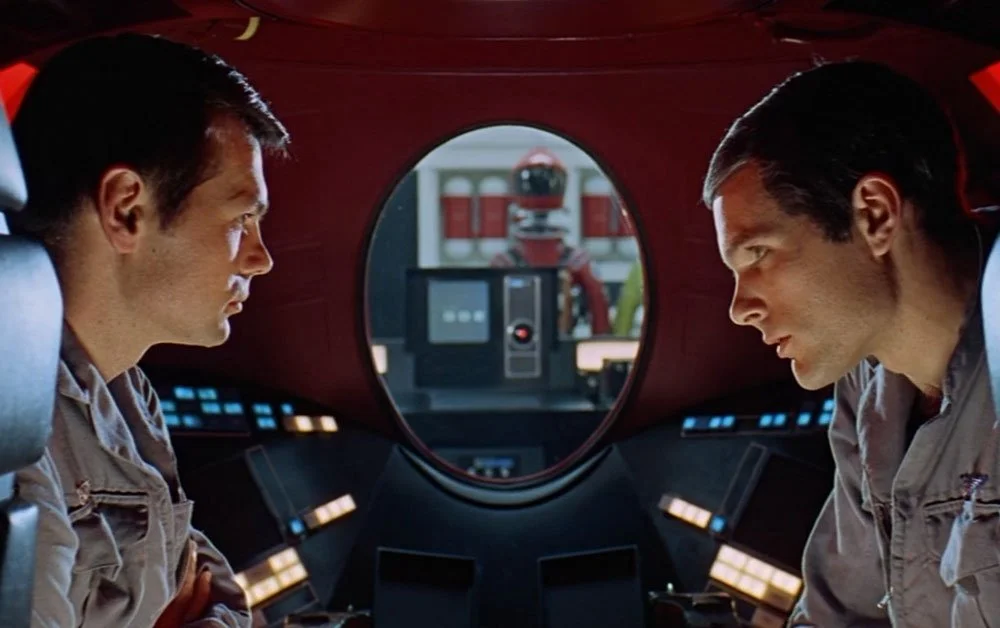

Frank and Dave aren’t convinced. They go into an EVA pod to have a private conversation about the possibility that HAL is malfunctioning (and the possibility that they’ll have to disconnect him). But HAL manages to follow along from outside the pod by reading their lips.

Meanwhile in Adventure Time, Jake pulls Finn and Princess Bubblegum into the other room to have a trust huddle. Finn and Jake are now convinced that James is a saboteur. Princess Bubblegum insists that “it’s not James” (and on our first viewing we do not register that she’s essentially admitting that there is a saboteur).

“What’s not James?” asks James, who has inserted himself into the trust huddle.

When I rewatched 2001 (and then rewatched “James”) to investigate this influence, I was expecting to find visual similarities. Usually homages to (the Jupiter mission segment of) 2001 quote the architecture of Discovery 1, the octagonal corridors or the womblike computer room. Instead, “James” quotes a significant portion of the story itself: The research mission encounters a problem with the radio. An attempt to fix the radio reveals that a crew member is unreliable. The rest of the crew has a secret meeting about this unreliable crew member, but he manages to involve himself.

In 2001, HAL responds to the “overheard” conversation by killing Frank, killing some other scientists who are in hibernation, and attempting to kill Dave.

In “James,” more of Finn’s attempts to save the day are foiled by apparent sabotage. At last he sees that the only way for any of them to survive is for one of them to “eat the big one.” As he heroically attempts to volunteer, Princess Bubblegum knocks him out with a wrench. Then she knocks Jake out with a wrench.

Finn regains consciousness, and from his perspective we see Princess Bubblegum conversing indistinctly with James. This isn’t a case of characters roles and actions matching between movie and show, but I do think it’s inspired by the POV shots of HAL watching Frank and Dave’s lips move.

James eats the big one, allowing Princess Bubblegum to carry Finn and Jake to safety. She reveals that she was the saboteur all along: “I calculated the chance of success for every possible escape plan, and none of them were going to work.” Finn was right about sacrificing one person to save the rest, but James was literally expendable in a way Finn wasn’t: With a sample of James’s candy biomass, Princess Bubblegum can clone a new James.

The twist reveals the true nature of the 2001 homage: We were led to believe that James (constantly whirring and pop-and-locking, as if he aspired to be a computer) was the HAL 9000 figure, cutting off communication and endangering the mission out of malintent or perhaps incompetence. But really it was Princess Bubblegum, foiling Finn’s attempts for the good of the mission—because she knew better, because she had done all the calculations. Finn volunteered to sacrifice himself out of emotional human altruism; Princess Bubblegum decided to sacrifice someone else based on cold utilitarian analysis.

Analysis (you can skip the rest of this)

Readings of 2001: A Space Odyssey

The relationship of “James” to 2001 hinges to some degree on our understanding of HAL’s internal state in 2001. I think there are three ways of reading this aspect of the story: two naïve readings that you can get out of the film itself, and a more interesting reading that relies on exterior information. But they’re all pretty similar to each other, so bear with me while I belabor some points:

The first naïve reading, the one that requires the least inference, is that HAL really did make a mistake when he detected a fault in the AE-35 unit. Then he saw the astronauts discuss the idea of disconnecting him based on this error, so in the interests of self-preservation he tried to kill them first. (We might say this corresponds with the notion that an Adventure Time viewer might briefly entertain that James destroyed the radio and lost the flare gun out of sheer stupidity.) This is not a very interesting explanation; for one thing, it puts the whole story at the mercy of an everyday computer glitch.

The second naïve reading demands that we “deduce” that HAL fabricated the AE-35 fault as part of a preconceived plan to cut off communication with Earth and eliminate the human crew so that he could complete the mission on his own. The film takes care to establish how much the humans rely on HAL (so much of the sparse dialogue is simply asking him to open doors) and it’s easy to imagine that he resents his subservient position. (This would correspond with the theory that James was deliberately sabotaging the mission for some reason.)

The third reading doesn’t get much support in the text of the film, but it’s made explicit in the novel and the sequel. It goes like this: HAL was programmed to supply the humans with any information that would benefit the mission, but he was also given specific orders to conceal the true nature of the mission from them. The only way to reconcile these conflicting instructions, according to HAL’s heuristics, was to kill all the humans. On this reading, the scene where HAL reports the AE-35 fault right after trying to interview Dave about the “extremely odd things about this mission” becomes much more dramatic. (The film does reveal that HAL knew the secret purpose of the mission all along, but it doesn’t give the viewer any reason to connect that to him murdering everybody.)

In the naïve readings, HAL 9000 murders people to satisfy distinctly non-robotic varieties of self-interest; really, he is acting like a human. But if his actions are simply the logical output of his programming, then he’s acting like a computer. And it’s this third reading that I think informs the thematic impetus of “James,” where the drama isn’t motivated by incompetence or malice, but by a rational person acting rationally—the story uses its 2001 homage to obliquely compare Princess Bubblegum to a computer.

Readings of “James”

“James” serves a larger agenda in this era of Adventure Time, which was concerned in large part with developing the tyrannical angle of Princess Bubblegum’s character. The episode calls her methods into question a bit artlessly when Finn asks out loud: “Is this right or wrong? I can’t tell.”

Some people are inclined to read Bubblegum’s questionable actions in “James” and other episodes as a critique of utilitarianism. I don’t think Adventure Time is equipped to make any meaningful statement on real morality, on the real efficacy of real utilitarianism. For one thing, the decision-making information that the characters (and audience) have access to is entirely at the whim of the writers. Bubblegum claims that she can calculate the outcomes of all Finn’s plans, which in a realistic story would be characteristic of a deluded, truly villainous utilitarian. But in the world of Ooo, this claim is just as likely to be completely reliable as it is to be hubristic folly.

The decision-making information itself is completely arbitrary as well. Bubblegum’s own solution relies on her ability to make a perfect, full-grown clone of James out of a chunk of his “candy biomass”—and indeed she can do all this, in the space of about a week. Applying human morality to her reasoning or extrapolating from her actions to a statement on human morality are both wastes of time, because Princess Bubblegum has access to information and choices that can’t be directly related to our experience, because Princess Bubblegum exists in a world of made-up nonsense.

The 2001 angle doesn’t have any real bearing on the lucky coin James carries. Its main function is to serve dramatic irony: We know James will die, but he believes he’ll be fine, because he has his lucky coin. Then he generously gives the coin to Jake; of course, without his lucky coin, James dies within minutes. But the episode’s title card puts a special focus on the coin and its engraving: The obverse bears Princess Bubblegum’s portrait and the motto “SCIENCE IS A-OK.”

Adventure Time likes to focus on conflicts between science and magic (where “magic” can stand for “intuition” or “organized religion” or “spirituality,” depending on the episode), but this is another area where the show has difficulty saying anything really meaningful. In Ooo, technology really is advanced enough to be indistinguishable from magic (the kingdom of candy-people ruled by an eternally teenaged princess made of bubblegum? that’s science) and in order to make us care about any strife between the two, first the show has to explain to the viewer which one is which. Princess Bubblegum insists in “Wizards Only, Fools” that all magic is just science we don’t understand yet, but it’s not clear that all the shows’ writers agree. In practice, magic might be truly inexplicable, or contingently explicable, or identical to technology, on an episode-by-episode basis.

When “science” is treated as a metonym for rational, dispassionate thought, as opposed to “magical” intuition and feeling your way through problems—the “crystal certainty” of Finn’s heroic speech—then Adventure Time is able to make much more compelling statements, on the level of character. Finn “can’t tell” whether Princess Bubblegum did the right thing, not just because the outcome of her actions doesn’t fit his idea of heroic narrative, but because her priorities and reasoning are foreign to his heroic paradigm. The imagined ethics of cloning a walking wafer cookie are amusing but ultimately pointless; Finn’s disillusionment with his princess is what makes the drama of the character relatable and compelling.

Oceans of digital ink have been spilled over questions of whether Princess Bubblegum is Good or Bad. In a sense, these interminable comment threads are themselves the correct answer, because the “truth” is that Bubblegum is constructed to be complex and irreconcilable and therefore interesting to watch as her own character, while also challenging Finn’s black-and-white worldview and deepening his character. If we insist on passing a single, straightforward judgment on her, we are choosing to be as naïve as the Finn of the first four seasons.