When I act as Dungeon Master for my little D&D group, I’m always searching for puzzles to use in my campaign. I steal ideas shamelessly, as mandated by the DM Code, but my constant googling doesn’t always yield puzzle concepts I can use. I have very high standards. Plus, I play on Roll20.

Roll20 is great, obviously. If you want to play any tabletop RPG online, Roll20 has all you need. It is great. For a while, though, I thought Roll20 had no applications for puzzles whatsoever. After a while I changed my mind; I began to think that the only application it had was for jigsaw puzzles. The longer I used it, the more possibilities I saw. I feel a duty to share what I’ve done so far, so that other DMs can steal my ideas—also, I want to share what I’ve done so far, because I am proud of myself.

Jigsaw Puzzles

To make a jigsaw puzzle in Roll20, you just need to divide an image into a bunch of pieces, upload them in the media manager (or whatever it’s called), and drag them all onto a Roll20 page as tokens.

During a Gothic adventure, my players got a chance to reassemble a sad little gargoyle:

After I found the source image, I carved it up in an image editor with the freehand lasso tool, cutting and pasting each piece into its own file. That was a little tedious. Then I added all the pieces to the Roll20 board as tokens; then I had to make each of those tokens controllable by the players, which was kind of tedious as well.

(When your pieces are irregular like this, you’ve got to go into the page settings first and disable the grid! Otherwise the pieces will snap to the grid!)

You can see in the above image that the gargoyle pieces did not fit together perfectly. This is because they weren’t all perfectly to scale with each other, because sometimes Roll20 does some sort of weird resizing to tokens when you add them to a page. Sorry!

(You can get around this problem if you make all your pieces line up with Roll20’s default 70×70-pixel-lined grid! Then you can use the snap-to-grid feature to your advantage!)

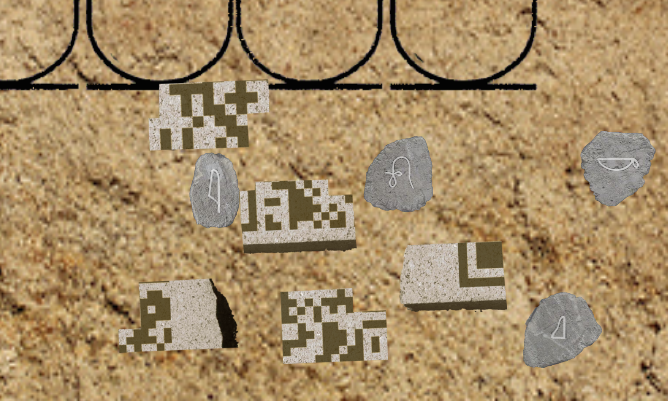

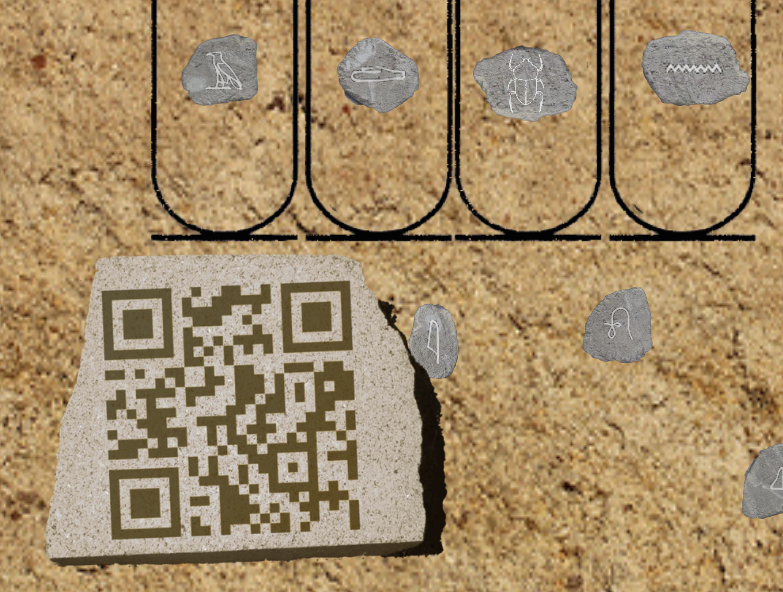

It’s a real bad problem if the pieces in question need to line up perfectly, as in this puzzle from a mummy’s tomb:

Not all the pieces are in this image, but you can tell what’s going on. This puzzle was supposed to assemble into a QR code. (A QR code in a mummy’s tomb makes very little sense—about as much sense as most of the English wordplay-centric riddles that players see carved above doorways all over Toril.) My players tried their level best to get the code to fit together, but it was hopeless: Not all of the pieces were the right size, and I couldn’t manage to resize them correctly on the fly. Eventually I had to upload the image of the completed puzzle myself, so that my long-suffering players could experience the thrill of scanning a QR code for once in their lives.

That being said, jigsaw puzzles do work out pretty well in Roll20. It’s a lot more fun than rolling an Intelligence check. Players can participate simultaneously, working on their own or as a team as the need arises. And, most importantly for me, the abstraction feels like the activity it represents. The players are putting the thing together “for real.”

That being said, jigsaw puzzles do work out pretty well in Roll20. It’s a lot more fun than rolling an Intelligence check. Players can participate simultaneously, working on their own or as a team as the need arises. And, most importantly for me, the abstraction feels like the activity it represents. The players are putting the thing together “for real.”

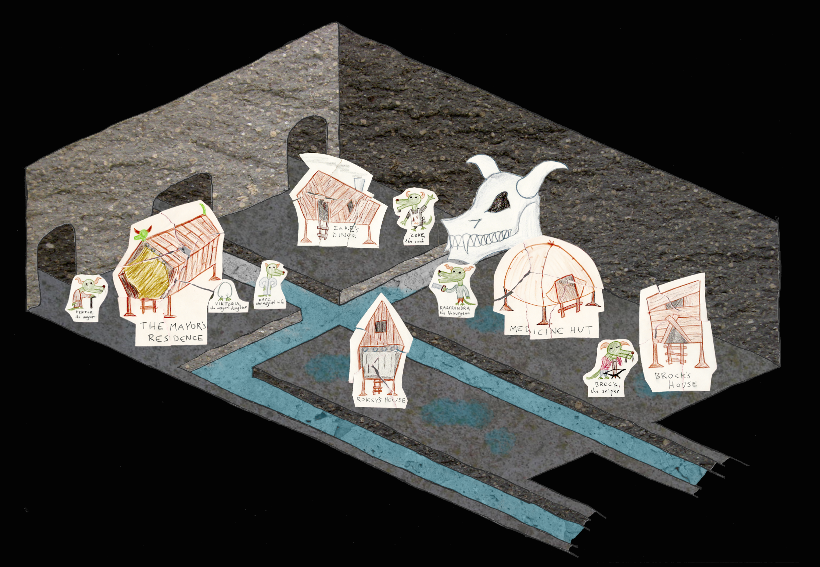

My favorite jigsaw puzzle that I’ve run requires some background information. The party was cleaning up an old sewer, where they found a kobold settlement. They became friends with the kobolds, but then they accidentally flooded the sewer. When they returned to Kobold Towne after almost drowning, it looked like this:

The PCs immediately started assisting with the reconstruction efforts, and soon Kobold Towne looked like this:

Everything was back in its place. But if that house is Roksy’s house, where’s Roksy? By finishing the puzzle the players learned that one of the kobolds was missing, which set off a sidequest to find her in a much more interesting manner than the mayor simply saying “Hey, I don’t know where Roksy is.”

Hidden Image Puzzles

This is basically impossible to explain.

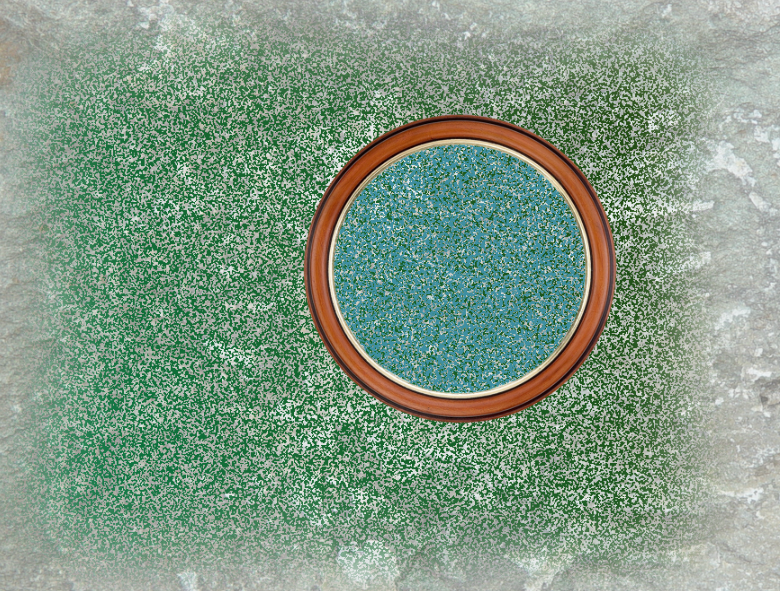

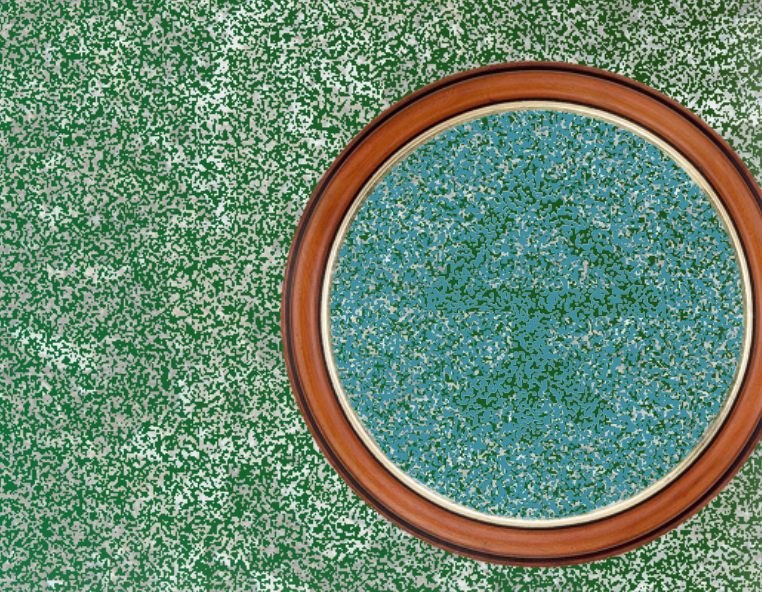

The party found a tiny portal, and it fell to them to close it. They were given a Lens of Planar Stabilization (the blue thing).

The players thought they were looking at a Magic Eye puzzle. No! That would also be cool, though.

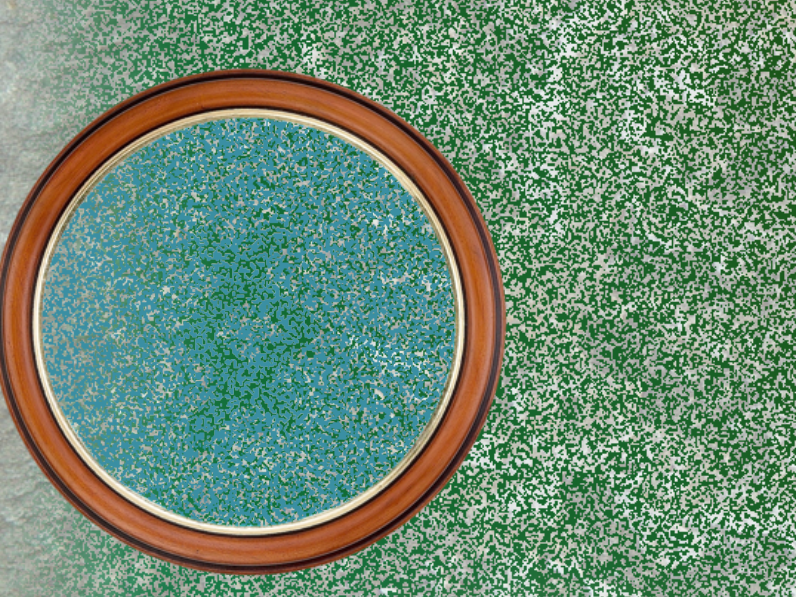

By moving the lens around the surface of the portal (here is a case where you definitely want snap-to-grid enabled), the players made symbols appear:

Figuring out what was up with these symbols was the key to closing the portal; I won’t bore you with the details.

The principle involved was lifted from the “Crypto-Tokens” designed by Stephen Shomo. If you want to try something similar but you don’t have time to put the whole thing together yourself, you can buy his token set. I would explain how to do it yourself, but it’s really complicated and I doubt I could remember all of it!

Memory (or: “Concentration”)

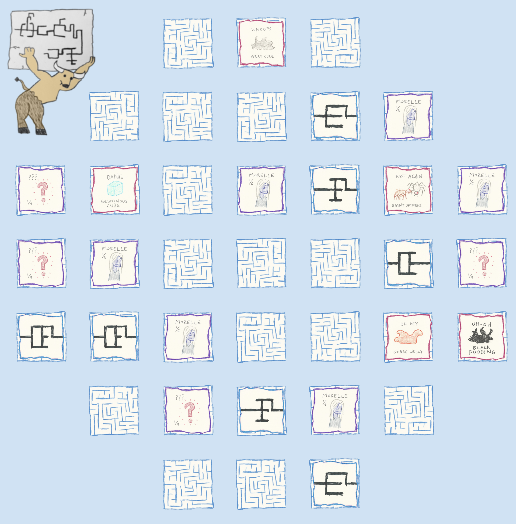

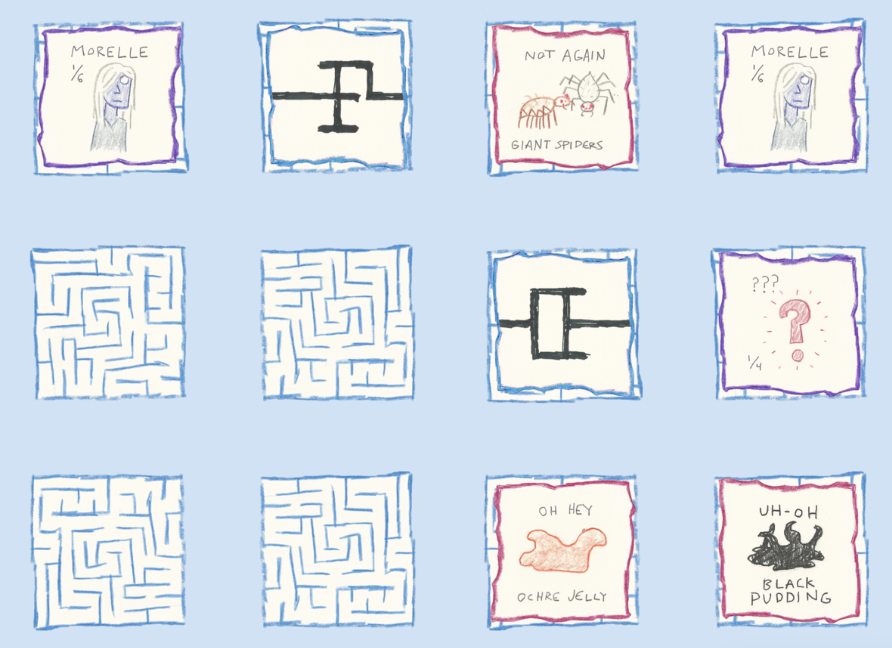

I stole this idea from this guy, who stole it from this guy. The players needed to navigate a maze. They weren’t looking for the exit; they were looking for two people who were lost in the maze.

The board looked like this:

Here it is zoomed in a bit:

Exploring the labyrinth worked more or less like a game of Memory. At the beginning, all the pieces were flipped over (only the anonymous “maze squares” were visible). Players took turns picking pieces to flip.

Exploring the labyrinth worked more or less like a game of Memory. At the beginning, all the pieces were flipped over (only the anonymous “maze squares” were visible). Players took turns picking pieces to flip.

Remembering the locations of matching tiles and eliminating various possibilities represented the gradual mastery the characters had over the maze; flipping over the wrong tile and losing progress represented getting turned around and ending up back where you started. This abstraction is intended to feel like a maze, and represent a massive labyrinth of a scale far too huge to play the normal way, on a map with a maze on it.

How do you flip tokens in Roll20? Well, Roll20 has a function where you can assign different “faces” to a token by attaching a rollable table to it. That sounded to me like a lot of work, though. I didn’t do that. I just made the “back” and “front” of each tile into two different tokens, and I right-clicked the one on top and pushed it “To Back” whenever they needed to be flipped.

There was some discussion in the linked Reddit threads about the rules for this type of Memory variant. I decided to run it like this:

- One person flips a tile, then another person flips a tile, and so on.

- If a full set of matching tiles (usually 2) gets flipped, they get to stay flipped permanently.

- If a bad tile (a trap or combat encounter) is flipped, then the party has to deal with that event.

- If the bad event is resolved such that it makes sense for the party to remember where they are in the maze, then progress is preserved; otherwise, the preceding face-up tiles are flipped face-down. The bad tile stays flipped face-up.

- Tiles representing the objectives (in this case, the people lost in the maze) are in sets of 4 or 6. I don’t know why I picked those numbers. Only when the full set is flipped in sequence is the objective reached, and then the full set remains flipped.

This last rule makes the important stuff harder to find, and in my case led the players to consider two different strategies: Do we start out by eliminating the easy (but useless) tile pairs, or do we trust our memory enough to focus exclusively on finding the important tiles?

The distribution of card types was:

- 18 “progress” (“uninteresting”) tiles in 9 pairs. The symbols on these tiles were from a minotaur alphabet the players had seen before: easy to confuse, unless you had been paying attention!

- 5 combat encounter tiles.

- 14 objective tiles: one set of 6 and two sets of 4.

The rule I used for the negative events worked out all right, I think. I will say, however, that if you use the exact numbers I did, the players will almost certainly hit every negative event before finding an objective—because to find any one objective you have to look at basically every tile at least once. Five is a lot of combat encounters, too. If I could do it again I would reduce it to three.

In Conclusion

Please steal these puzzles.